Folks who live along Irwin Creek and its tributaries used to swim, fish, even hold baptisms in the waters. The city once used it for drinking water. But runoff from streets, pollution from aging sewer pipes and heavy metals from an industrial past today make the creek one of the city’s most troubled. Yet, hope remains for a better future.

One of its first tendrils begins in Ernest and Misty Eich’s backyard in northeast Mecklenburg County, a trickle you can jump across.

There, the creek curls like a question mark through a ravine’s mossy banks, beneath towering tulip poplars.

Ernest, 39, and Misty, 37, often follow the stream with their dogs, Magnum and Abigail, as the waterway leaves the shelter of their six acres to join other tributaries in Ribbonwalk Nature Preserve.1 There, the Eichs watch the stream, whose headwaters they steward, officially become Irwin Creek.

From Ribbonwalk, Irwin gathers strength and pours itself alongside Interstate 77 south, concealed from commuters’ view by curtains of kudzu, secret within steep banks. The stream reaches the heart of Charlotte and embraces its west side, moving south until it finally links with Sugar Creek near Billy Graham Parkway.

Irwin’s waters once slaked the thirst of a growing city. Its springs nourished an African-American neighborhood as it took root. Its pools cradled fish, coached swimmers, baptized believers.

But nurturing a city came at a cost.

As it flows from a nature preserve to an interstate, embracing uptown and the west side, Irwin carries in its current a city’s missteps – pollution from aging sewage pipes, heavy metals from an industrial past, runoff from acres of asphalt.

Despite all this, those who know the stream well say Irwin still holds beauty and promise. It embodies all the ills of an urban waterway, say its advocates. But Irwin Creek is no lost cause.

“You can be frustrated with work and things going on in your life but when you come here, it’s a stress reducer,” says Rickey Hall, Reid Park Neighborhood Association president. “You can listen to the water flow over the rocks.”

Little Sugar’s lesser-known twin

Charlotte is a town founded on a hilltop – the reason Charlotteans call their downtown “uptown,” says Tom Hanchett, historian with Levine Museum of the New South. Native American trading paths became early roads, following the ridgelines, away from the creeks and their flood plains. Imagine Charlotte as a sheet of writing paper, Hanchett says. “Sugar Creek and Irwin Creek on are on the margins, and Charlotte is between the two.” 2

Irwin Creek is the lesser-known twin of Little Sugar Creek and a waterway whose slip from prominence in the life of Charlotte is highlighted by its very name. Pore over the oldest maps of the county, and you will find no Irwin Creek. 3

The waterway was there. But until the early 1900s it was called Big Sugar Creek, 4 named, like its sibling to the south, for the Sugaree or Sugaw Indians who once lived nearby. The creek’s new name honored a local landowner. And even as it lost its original name, the stream was sliding in status.

In the early 1880s, Charlotteans got their first publicly supplied drinking water from Briar Creek and later from Little Sugar Creek. It wasn’t always obvious that the murky creek water was a better option than water from privately owned wells.

“Often, Charlotte citizens could not tell the difference between a glass of water and a glass of cider,” said William Edward Vest, appointed superintendent of the Charlotte Water Works in 1910. 5

The growing city needed more – and better – water, and around 1905, it turned to Big Sugar, today’s Irwin Creek. Charlotte pumped raw water out of Irwin into a now-defunct filtration plant that could handle 5 million gallons a day. But by 1910, when Vest began supervising the water flowing from creeks to 34,000 city residents, trouble loomed. 6

“The situation is perilous,” the July 29, 1911, Daily Observer reported. “[T]here was nothing more than a ribbon of water trickling … all that remains of the much boasted Irwin’s creek of former years.”

In the summer of 1911, the Piedmont skies snapped shut. Irwin’s waters slowed to a crawl. City reservoirs dipped dangerously low.

“Water supply shrinking,” a Charlotte Daily Observer headline warned. “[T]he deficit will constantly increase until there is rain, and when that will be no man knoweth.” 7

A hastily summoned water commission urged Charlotte residents not to “use a drop more water than is essential,” the paper reported.

The city banned lawn sprinkling. Some residents sneaked water to their struggling lawns anyway – and police confiscated their hoses. A few wells still bubbled in town, drawing long lines of people toting bottles, jugs and kegs to fill. The city decided to erect a building around a spring in Independence Park to better capture the water, despite a local physician’s warning that the water was unsafe to drink. In desperation, the city turned off the tap. Water came on for just a short part of the day.

“Many citizens will recall the commotion in Charlotte households at certain hours as the [residents] hastened to fill up the receptacles of all kinds, bath tubs, etc…[calling] ‘Hurry up, it’s almost time to cut the water off!’ ” Vest said later. 8

But even the shutdown wasn’t enough.

“The situation is perilous,” the July 29 Daily Observer reported. That week, Irwin Creek’s waterworks pond was drained, leaving a crust of black sludge that looked “weary beyond description,” the paper said. “[T]here was nothing more than a ribbon of water trickling through it, all that remains of the much boasted Irwin’s creek of former years.”

With nowhere else to turn, the parched city called on railroad tank cars to haul in water from Mount Holly, Asheville, Gastonia and Columbia. 9

For Irwin Creek, it meant the beginning of the end of its days supplying drinking water. A chastened Charlotte laid pipe to the Catawba River and by spring 1912, river water began replacing creek water in city taps. 10

Waters for body and soul

Irwin might have lost its role of supplying drinking water to a whole city, but in the decades that followed, it still loomed large in the lives of local residents.

In the 1930s and ’40s, African Americans built homes in the newly created Reid Park neighborhood near Irwin Creek, eager for their piece of the American dream. Early on, homeowners lacking wells scooped cold water from an Irwin spring to drink, cook with and bathe.

To find the spring today requires a chancy climb down a steep, rock-strewn ravine hiding half-buried tires. A broken slab of concrete shelters a dry depression in the ground where the spring once bubbled.

Curley Hall is 83. Her family has lived in the west Charlotte neighborhoods near Irwin Creek for at least several generations. Her grandmother and uncles lived on Ross Avenue, not far from today’s Clanton Park. The creek and its tributaries were part of her family’s intimate daily life, she says. The waters sustained them, body and spirit.

“I was baptized in that creek,” says Hall, who was then a member of Shiloh Baptist Church, now New Shiloh, on Elmin Avenue. 11 “We would walk from the church about a mile… down the hill at the end of Amay James (Avenue).” There, the waters of a branch of Irwin flowed near the road, close to the main body of the creek. She wore a long white baptismal gown, Hall remembers, and stepped down into the water to meet the waiting pastor.

Charlie Mitchell, 63, grew up on Watson Drive west of today’s Revolution Park. “We were six boys and three girls,” says Mitchell, stopping one morning as he rode a bike through the area. The creek’s feeder streams bordered his neighborhood. “We had our baths down there. I waded in it. It was just fun.” 12

For some, especially the children, Irwin quenched a thirst for adventure. Oaklawn neighborhood resident Mable Latimer, 79, recalls how the creek – and its resident snakes – scared her a little. But she’d watch as cousins and friends would jump in to swim and show off.

“The guys would try to be little heroes and show us they could walk in the creek, and every time, someone would push somebody,” laughs Latimer, a graduate of West Charlotte High School. 13 “They had a big pipe that went across the creek. A lot of kids used it as a bridge.”

Contamination gets worse

That close contact with Irwin’s water was probably risky decades ago, but as time went by, Irwin grew dirtier. Before the Irwin Creek Wastewater Treatment plant was built in 1927, residents dumped raw sewage directly into the stream. In years past, even the treated water discharged from the plant could be full of fecal coliform, bacteria from human waste. 14

Today, pet waste washed from yards during strong rains spreads fecal coliform into Irwin. Aging sewer pipes – which almost always are installed along creeks so that gravity can move the sewage more easily – can leak.

The state classifies Irwin a “Class C” waterway. 15 That means people should be able to wade in the water and fish, and it means the stream should support aquatic life. 16 It’s the classification for all of Charlotte’s major urban creeks.

“All of them are failing that grade,” says Daryl Hammock, Charlotte Storm Water Services assistant division manager.*17

Irwin is fed by a web of tributaries, everything from the tiny stream in Ernest and Misty Eich’s back ravine to large waterways like Stewart Creek whose tributaries thread through much of northwest Charlotte. To truly restore Irwin, many miles of those streams would need to be stabilized and the runoff from thousands of acres of asphalt would need to be filtered.

It’s not just fecal coliform that dirties Irwin. Copper from brake pads washes into the creek from roads. Toxic metals such as zinc and lead, the unwanted legacy of an industrial past, seep from soils. 18

In years to come, Irwin will benefit from two projects within its watershed, on Stewart Creek, says Hammock. In one case, a new, meandering creek bed will be dug alongside a scoured-out, artificially channeled existing section of Stewart, with riffles and bends to slow the water and plantings on the banks to slow runoff and shade the stream.

Those changes will filter pollutants and should ultimately improve Irwin. And when sites along Irwin get redeveloped, they are subject to a 2008 ordinance that requires pollution-laden water sheeting off roofs and pavement to be filtered. The changes are incremental, but they are moving in the right direction, Hammock says.

“This is a really, really long term restoration approach. It took two centuries of harming creeks to get them the way they are now,” says Daryl Hammock, Charlotte Storm Water Services assistant division manager.

“It won’t take just a few projects,” he explains. “This is a really, really long term restoration approach. It took two centuries of harming creeks to get them the way they are now.”

Two centuries – and a lot of road building. When Cam McNutt studies a map of Irwin Creek, he sees a lot of reasons Irwin isn’t cleaner.

“I can just look at this thing, and there is overpass after overpass and highway after highway,” says McNutt, environmental program consultant at the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 19

“It’s probably underneath a hundred roads.”

A series of specialized tests in 2014 to determine the source of the fecal contamination in Stewart Creek found some instances where fecal contamination was not a problem, but in places where it was, human feces were the predominant contaminant, suggesting a problem with sewer lines. (In one tributary, dogs were the main problem.) 20

Fixing sewer pipes will help Irwin, McNutt says, as would a program to stop the infiltration of pet waste and any redevelopment along the creek that’s designed to stop pollution-laden runoff. It’s a daunting task.

“Irwin Creek, it doesn’t seem like you can do much,” McNutt says. “But if you raise awareness, when people go out to a natural stream they don’t turn it into Irwin Creek.”

seeking its past, hopes for its future

But for Rickey Hall, Irwin Creek is more than a morality tale.

Hall, Reid Park neighborhood activist and the son of Curley Hall, leads a visitor along Irwin Creek one scorching summer day, pushing through stands of weeds and briars to peer down at Irwin, hoping for a glimpse of his past.

The creek, he says, is “a vital link to adding an amenity of value to public health, the walkability, all of these amenities along a natural waterway. Long before (neighborhoods) Arbor Glen or Dalton Village were there, this was a playground for kids like me.” 21

It sometimes still is. Hall and his visitor come upon a group of excited preschoolers with their teachers, climbing up from the creek banks. “We saw an ALLIGATOR!” one child says, eyes wide. “It was swimming in the water!”

The children’s teachers keep them close, well out of the water. But years ago, Hall and his friends had no such restrictions.

“My first swimming pool wasn’t the (now-closed) Revolution Park swimming pool, it was Irwin Creek,” Hall says. He and his buddies caught large turtles in the creek, flipped over rocks to spy on salamanders. They cut through what was then pastureland alongside the creek to swing on vines over the water, played GI Joe in the underbrush, and snacked on wild plums and blackberries.

“There is no reason why this should be so polluted,” says Rickey Hall, Reid Park Neighborhood Association president.

“This area deserves the same attention as any other part of the community,” Rickey Hall says. “When you pull back the layers of the community and look at the natural amenities, this” – here he points down at the creek, wide and shallow, sparkling in the sun – “it’s a jewel.”

Hall believes Irwin is polluted in part because his west Charlotte neighborhood “is considered a community of least resistance.” Residents, he says, have to raise the profile of their community.

“There is no reason why this should be so polluted,” he says. “You think about things like environmental racism and public health exposures. To me (the creek) is a natural extension of people who are here. You can be frustrated with work and things going on in your life but when you come here, it’s a stress reducer. You can listen to the water flow over the rocks.”

Hall makes his way gingerly down a bank draped in wild mustard to stand next to the water. Behind him, a hooded warbler sings its rocking-horse-rhythm song.

“Now you tell me this isn’t beautiful,” he says.

too polluted for kids to touch

When they first arrive at Anthony Shaheen’s after-school nature program, many of the kids from west Charlotte’s Reid Park Academy are skeptical about what Shaheen has to offer. Video games excite them. Nature? Not so much.

But Shaheen, an outdoor recreation specialist with Mecklenburg Park and Recreation, knows his audience. He’s been running his Urban Outdoor Connection program in west Charlotte for several years, helping urban kids learn to love the natural world. If there is a single magic ingredient to making that happen, it is this: running water.

Shaheen meets the kids at the Arbor Glen Outreach Center in Clanton Park. When he began the program, he would guide the dozen or so children down the slope to Irwin Creek. We’re going to do a stream study, he would announce. The children, who range from kindergarten to eighth grade, would pull on boots, grab nets, and nervously follow Shaheen into the water.

The transformation didn’t take long. The kids grew excited, turning over rocks, searching for dragonfly nymphs and caddis fly larvae – the macroinvertebrate insects whose presence reveals clues to a stream’s health. They would stir the stream to capture insects in kick nets, eager to uncover signs of life. And they would play, spying out animal tracks and building dams.

The kids “absolutely love it,” Shaheen says. “They can’t get enough of it. It’s hard to pull them out of the creek.” 22

All of that changed a year ago when Shaheen discussed the popular program with a supervisor. Irwin Creek, he was told, is rated not fit for human contact – too polluted for kids to touch. The stream was off limits.

“The group that I’ve done most of the work with were looking forward to (the stream study) every single year,” Shaheen says. “When I told them they didn’t have the ability to do that, they were pretty disappointed.”

Shaheen still runs nature camps for students in the Irwin Creek watershed. But now, when he wants them to experience a creek, he has to bus them southwest to McDowell Nature Preserve, where streams still run clean.

Losing contact with a creek that is their own means west Charlotte kids lose a way to understand the connection between landscape and life, Shaheen says.

“There’s a huge disconnect. If you ask them where their water comes from, they’ll say ‘the faucet,’ ” he says. Children “don’t understand that the rainwater that falls in their backyard goes into Irwin Creek or Stewart Creek and winds up in the Catawba River and that’s where our drinking water comes from.”

can ‘clean’ be achieved?

Is cleaning a waterway like Irwin – so urban, so encased by roadways and riddled with pollution – just too ambitious?

“I wouldn’t say it’s too lofty (a goal) but it’s going to take a long time,” says Rusty Rozzelle, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services’ Water Quality program manager.*23 “We’ve made a lot of progress to that end, but we’re not there yet. The biggest hurdle is sewer, and in Charlotte all the sewer lines are by the creeks.”

The lines, Rozzelle says, “leak and break and clog and spill over …. (and) Charlotte has about 4,000 miles of sewer lines. Like all infrastructure all over the world, it’s aging and there’s not enough money to take care of. It’s just a daunting task.”

Christopher Matthews is Mecklenburg Park and Recreation’s division director for nature preserves and natural resources. When he looks at Irwin, he sees a large urban waterway that has suffered from close proximity to industry, roadways and countless homes.

“It’s a heavily impaired creek,” says Matthews. 24 Once, in a time lost to memory, Irwin was home to the famed Carolina heelsplitter, a critically endangered freshwater mussel today on the brink of extinction, Matthews says. Now, the only animals and insects living in Irwin’s waters are species that are “pretty tolerant of pollution.” As for a large-scale cleanup, the odds aren’t good. “Doing a big urban creek like that is really hard,” says Matthews.

Creek restorations depend on easements, and it’s a lot cheaper for a local government to clean up sections of a creek where it owns a lot of land. For much of its length, Irwin backs up to private property as it winds through neighborhoods. Restoring a section without fixing the upper stretches that wash sediment and pollution into it can mean the fix doesn’t last long.

But Irwin’s advocates agree the creek should not – must not – be written off.

“Basically, if we start giving up on polluted waterbodies, then we’re going to do less than protect them,” says Will Hendrick, associate attorney with the nonprofit Southern Environmental Law Center, which in the past has filed comments with N.C. DENR on behalf of Irwin and other Charlotte creeks. 25 “And (then) we’re going to basically imply that there’s some threshold where once our water is polluted, we’re just going to throw our hands up and stop doing anything.

“People should be able to use that water for the purposes the state has designated it. There is no lost cause.”

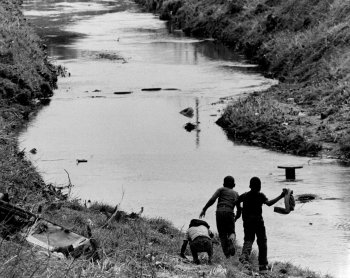

As it turns out, a lot of Charlotteans feel the same. Hundreds show up for Mecklenburg County’s Big Sweep creek cleanup every year to wade in muck and pluck trash from stream sites around the county.

At a September Big Sweep event on Irwin, Creek, Kathryn Moore, 30, and her 4-year-old son, Patrick, join other volunteers to don gloves and tote garbage bags along a stretch of creekside greenway.

“Bottles, piping, plastic bags, a sock…” says Moore, peering into her bag to tally the contents. Moore lives in the Plaza-Midwood neighborhood and this trip to the section of Irwin behind Ray’s Splash Planet has surprised her. “It’s a beautiful creek,” she says. “I didn’t even know this was here.”

Shaneka Moore, 21, not related, and Dania Asaad, 18, are also gathering trash this day. The Central Piedmont Community College students have hauled tires out of the creek bed. Despite the trash they found, says Moore, “it’s a really pretty creek.” 26

Asaad looked around her at the greenway bordering the creek. “It’s peaceful here,” she says.

Above the women, mulberry, pecan and black walnut trees cast their shade and blue jays shriek in the branches. Jewelweed forms a tangle near the water’s edge. Joggers and dog walkers stream past on the greenway. The dull roar of traffic from I-277 forms a wall of sound behind the scene, but not enough to disturb.

“The future is, things are getting better for Irwin and Sugar and all the creeks,” says Daryl Hammock, with Charlotte’s storm water services. “But it’s a very slow process, requiring massive investment, cooperation and time.”

How much time?

Hammock, in his 40s, considers. His grandchildren, he says, “will have a cleaner Irwin Creek, for sure.”

“It will definitely be better,” he adds. “Will it be swimmable and fishable? That’s the ultimate goal.”

*A note of disclosure: The Charlotte storm water education office of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services donated funds to assist with artist Stacy Levy’s educational project in Revolution Park, Passage of Rain, a part of the overall KEEPING WATCH on WATER: City of Creeks project.

- Interview with Ernest and Misty Eich, July 19, 2014.

- Interview with Tom Hanchett, Aug. 12, 2014.

- Mouzon map, copy held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room.

- “The Growth of the Charlotte Water Works Under William E. Vest,” by Joe L. Greenlee, held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room; for creek name change, also The Charlotte News, Jan. 18, 1979.

- “Interesting Carolina People,” by Mrs. J.A. Yarbrough, a profile of William Edward Vest, newspaper unknown, held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room.

- “Some High Spots in the History of Charlotte’s Public Water Supply,” Charlotte Water Department, held by Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room.

- The Charlotte Daily Observer, June 1, 1911.

- “Interesting Carolina People,” by Mrs. J.A. Yarbrough, a profile of William Edward Vest, newspaper unknown, held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room.

- “The Growth of the Charlotte Water Works Under William E. Vest,” by Joe L. Greenlee, held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room; for creek name change, also The Charlotte News, Jan. 18, 1979.

- “The Growth of the Charlotte Water Works Under William E. Vest,” by Joe L. Greenlee, held by Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, Carolina Room; for creek name change, also The Charlotte News, Jan. 18, 1979.

- Interview with Curley Hall, Feb. 26, 2015.

- Interview with Charlie Mitchell, May 6, 2014.

- Interview with Mable Latimer, April 2, 2014.

- An Evaluation of Fecal Coliform Bacteria Concentrations Up- and Downstream of the Irwin Creek and Sugar Creek Wastewater Treatment Plants in Mecklenburg County, 1998-2001, by Porche Spence and Jasper Harris, N.C. Central University Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, The North Carolina Geographer, Vol. 11, 2003.

- NC Division of Water Quality

- North Carolina Division of Water Resources – Surface Water Classifications

- Interview with Daryl Hammock, Feb. 26, 2015.

- North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources – 2014 Category 5 Water Quality Assessments 303(d) List

- Interview with Cam McNutt, Sept. 24, 2014.

- 2014, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services report, Microbial Source Tracking, Stewart Creek

- Interview with Rickey Hall, May 6, 2014.

- Interview with Anthony Shaheen, Feb. 17, 2015.

- Interview with Rusty Rozzelle, April 11, 2014.

- Interview with Christopher Matthews, March 25, 2014.

- Interview with Will Hendrick, Sept. 18, 2014.

- Interviews with Big Sweep participants, Sept. 27, 2014.