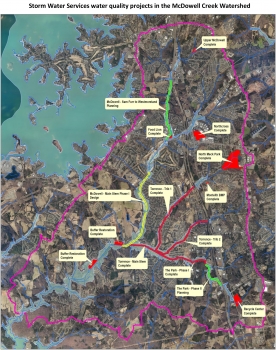

McDowell Creek drains 30 square miles of northwest Mecklenburg County, including much of Huntersville. Its waters flow into the drinking water supply for much of the county, Mountain Island Lake. That’s one reason it’s getting the full force of local water-quality attention, with restoration and cleanup underway.

If there is a dark side to development, you can find it in the waters of McDowell Creek. There, red clay runoff from Mecklenburg County’s runaway growth has clouded the creek, choking insects, smothering plant life. Worse, the creek and its tributaries pour into Mountain Island Lake, the drinking water source for much of Charlotte.

But if McDowell is a snapshot of what can happen when buildings go up and trees come down, it’s also a picture for what a community can do when it wakes up to a threat.

That’s because McDowell’s 75 miles of creek and tributaries – starting in Cornelius just east of Interstate 77 and draining much of northwest Mecklenburg County – are getting the full force of the city and county’s water-quality attention, with restoration and cleanup underway throughout the watershed’s 30 square miles.

“It was pretty dire.. People got used to seeing this big ditch up there and didn’t think too much about it,” says David Kroening, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services, who helps spearhead McDowell’s reclamation

Because some of the creek’s watershed remains undeveloped, there’s a chance for the community to do what it can’t inside the heavily built urban core: Stabilize a stream, restore habitat and set a course for a cleaner future.

“Our objective is to have clean water and preserve the areas around the creek,” says Huntersville Mayor Jill Swain. “It’s so encompassing. It’s not just the water but allowing the (surface) water to be filtered to the ground water.”

The problems for McDowell began in Mecklenburg County’s own version of a land rush. Much of the northwestern part of the county was still rural when the 1980s and ’90s brought an onslaught of development. In 1992, the town of Huntersville, which lies in the McDowell watershed, was home to about 3,500 people. Today the population is 52,000.

Asphalt replaced farm fields, sheeting runoff into the stream without the filtering benefit of fallow ground. Shorn of their trees, denuded banks crumbled. Sediment flooded McDowell’s waters, staining them rust-red, ocher-yellow. Seen from the air, parts of the creek have at times looked like nothing so much as a long, stretched-out mud puddle.

When John McDowell, son of Scots-Irish immigrant Charles McDowell, was given a land grant in 1753 along the creek that already carried his father’s name, his plantation included swampy forest into which the creek could have overflowed its banks harmlessly. In the following 200 years, subsequent farmers dredged, straightened and rerouted McDowell to drain farm fields.

Those ditching practices are now understood to be harmful, but at the time, the creek still had enough of a buffer around it – forest, fields – to keep it clean and full of insect, fish and animal life, despite those ditching mistakes. Then rapid development – neighborhoods, commercial strips, roads – eliminated that buffer. By the mid-1990s, the evidence was in: algae blooms, aquatic insect die-offs, contamination of waters in McDowell Creek cove of Mountain Island Lake.

A modeling study some 15 years ago forecast the expected build-out of Huntersville and Cornelius – in whose jurisdiction McDowell lies – and predicted what the creek would look like without intervention.

“It was pretty dire,” says David Kroening, lead project manager with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services’ engineering and mitigation program and one of the people spearheading the reclamation of McDowell.* Despite the bleak outlook, it wasn’t certain everyone realized the watershed’s future hung in the balance.

“People got used to seeing this big ditch up there and didn’t think too much about it,” says Kroening.

The town of Huntersville enacted tough new ordinances to require better water-protection practices for new development, requiring subdivisions to be built farther from the creek and allowing developers to increase density if they set aside more open space, says Swain, who served eight years on the town board before becoming mayor eight years ago.

Mecklenburg County, along with Huntersville and Cornelius, got to work restoring the damaged portions of the creek. There was no time to lose: By 2000, significant sections of McDowell Creek were damaged enough to land them on the state’s list of impaired waters.

“We’ve been working on it for about seven years up there,” Kroening says. “We’re about 15 to 20 percent of the way there.”

Stream restoration at McDowell has typically taken the form of stabilizing the channel so less sediment pours into the stream. And much good has been done.

“Up in McDowell Creek we’ve done a lot of stream restoration work,” says Rusty Rozzelle, program manager with Mecklenburg County’s water quality program. “We’ve got pictures of sections of (the) stream where the banks are as high as … (a) ceiling.”

After restoration, the creek’s abnormally high banks are cut back and new curves are cut to allow the ditch-straight creek to meander as it once did. That way, Rozzelle says, “The stream can access the floodplain and act like it’s supposed to.”

Restoration: BEFORE AND AFTER

It’s slow work. And expensive. Even after what Kroening ballparked at “in excess of $10 million” spent on McDowell restoration, key challenges remain, such as restoring segments of the creek that flow along private property. “In Huntersville, there’s an open-space requirement,” Kroening says. “Typically what developers do is deed (us) the floodplain, which is great because it provides us access.”

Access – and for the public, a window onto the water. When the county and towns create greenways along creeks in publicly owned floodplains, people notice the water and are more interested in caring for it.

“The presence of the greenway goes hand in hand with everything,” Kroening says.

As executive director of the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation, which advocates for water quality throughout the Catawba River basin, Rick Gaskins says he regularly gets calls from people who notice problems in lakes, rivers and creeks. And, he says, “Whenever a new section of greenway opens, we all of a sudden start to get a bunch of calls about that creek. Because all of a sudden people are seeing that creek.” [Footnote: Interview March 6, 2015]

Ultimately, what the community will wind up with, says Kroening, will be “green ribbons adjacent to our creeks and a fully functioning ecosystem – places to recreate and enjoy the wildlife that flocks there.”

“When people go up to Target or Lowe’s and see rain gardens they understand what we’re trying to accomplish,” says Huntersville Mayor Jill Swain.

Creek restoration, which can look ugly while it’s underway, is now understood by the community to be a force for positive change, says Swain.

Other water-improvement measures have also helped draw attention to the need to conserve and protect. “I believe we had some of the first rain gardens in the county,” Swain says. Rain gardens are plant-filled drainage areas that help filter parking lot runoff before it hits a stream. “We had developers volunteer to do that. When people go up to Target or Lowe’s and see rain gardens they understand what we’re trying to accomplish.”

Conrad Hill, 74, in 2005 bought a home in a neighborhood adjacent to Huntersville’s Birkdale Golf Club, within a shout of the 11th green. As he pauses in walking his dog, Sadie, Hill points to spots in his neighborhood that have standing water during heavy rains. McDowell flows under the street around the corner from his cul-de-sac.

“It’s a nice, quiet, pleasant area,” Hill says. But, he adds, “Development up here (has) exploded.”

And yet, some say, there’s still an opportunity to get ahead of continued growth and protect the creek and its watershed.

“We still have a chance at McDowell because it’s not fully built out,” says Christopher Matthews, division director for nature preserves and natural resources at Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation and a stream scientist by training. “If we can get the stream in good shape and do a good job of controlling storm water for future development, we have the opportunity to prevent the stream from degrading any further.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It’s so much more expensive to fix something that’s broken than to prevent it from being broken to begin with,” says Kroening of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services

“Even though McDowell and its tributaries are really impacted by sediment, by stabilizing them … we’ll also improve habitat for fish, aquatic insects and all the animals. Keeping the stream healthy, we have a better chance of keep anything else healthy.”

What is the lesson McDowell Creek offers to other communities concerned for their streams? Kroening has a ready answer.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” he says. “It’s so much more expensive to fix something that’s broken than to prevent it from being broken to begin with.”

Swain, who moved to Huntersville the weekend that Exit 25 on Interstate 77 was officially opened, says the region’s commitment to preserving water, air and a rural quality is part of what draws so many to live there. But along with the growth, work must continue on renewing McDowell Creek, she says.

“We can’t stop now,” says Swain. “We’ve made so much progress. And we have to keep moving forward. We just have to.”

UNC Charlotte Urban Institute graduate researcher Tenille Todd contributed to this article.

* A note of disclosure: The Charlotte storm water education office of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services donated funds to assist with artist Stacy Levy’s educational project in Revolution Park, Passage of Rain, a part of the overall KEEPING WATCH on WATER: City of Creeks project.